Randomness and Pacing

15 January 2026

This post contains vague spoilers for progression in Blue Prince, be warned!

In April this year, the video game Blue Prince exploded onto the scene, with many at the time calling it an early contender for Game of the Year. That sentiment seems to have held, with 86% positive reviews on Steam at time of writing, and many calls of “snub!" when it wasn’t announced as a nominee for the category at the Game Awards (though it was up for Best Debut Indie and Best Indie!).

For those who missed the buzz, Blue Prince is a roguelike puzzle game about exploring a mansion that changes each time you enter. Every time you walk up to a door, you have a choice of 3 rooms to draft. Your goal is to get to the mysterious room at the back end of the mansion, without blocking your path with dead ends and locked doors.

Despite the hype, there were naysayers (myself included, I must admit). It’s a frustrating game at times, mainly due to the fact that progression is locked behind randomness. The game keeps you busy by handing you lots of different leads, but progression towards the central objective is locked behind finding a specific room that can only appear randomly. I never got that room, it was actually developer Tom Francis’ video about the game that told me this room even existed. After multiple consecutive runs with no progress, learning that there was nothing I could do besides get lucky was the final straw that made me give up.

I really liked how Bluesky user wombburn put it in this post, “there's so much about blue prince that is simultaneously held back by yet which would not be nearly as impactful or engaging without the "roguelike" elements.” This design paradox is so interesting to me, and I’m not sure if I know the way out just yet.

I actually had a similar but opposite experience when playing The Librarian’s Appentice, a solo TTRPG by Almost Bedtime Theater. TLA is built on the Firelights system by Fari RPGs, which I’ve admired from afar for ages because it released just as I was getting into the indie RPG scene.

TLA and Firelights see the player travelling across a map made out of cards, with each card representing a different location. The goal of each game is to find 6 face cards. In Firelights these are beacons, in TLA these are books for you mentor.

Here is an overview of the cards I played in Librarian's Apprentice:

4, King, 8, 7, King, King, Queen, Jack, Jack, and the game was over.

The first half of the game was nicely paced, with a face card coming out every 2 or 3 cards. It felt a little jarring when the first card I moved to was a face (the 4 was where I started), but getting two non-faces afterwards smoothed out the pacing nicely. Then, in the second half, I got nothing but faces! Every time I discovered a new region, I was thinking “surely this won't be another face card,” and I was wrong every time! I thought I'd settled in for a game that would take 2-3 times as long, but that wasn't how it played out in the end.

Both of these moments reminded me of a similar problem I had when making my TTRPG Goodbye, World </3. Goodbye World is a game about a dying mech and the pilot that is stuck inside. The Pilot speaks but the Mech can only communicate by typing, and their messages are running out. The mech starts by rolling 3d6 to determine how many messages they can send, when that runs out they roll 2d6, then 1d6, then they die.

However, before this system of rolling for messages, the first version of Goodbye World used a death saves mechanic. Every time you sent 5 messages, you'd roll a 50-50 death save to see if you lost a life. If you failed, you'd roll every 3 messages, then 1, then you'd die.

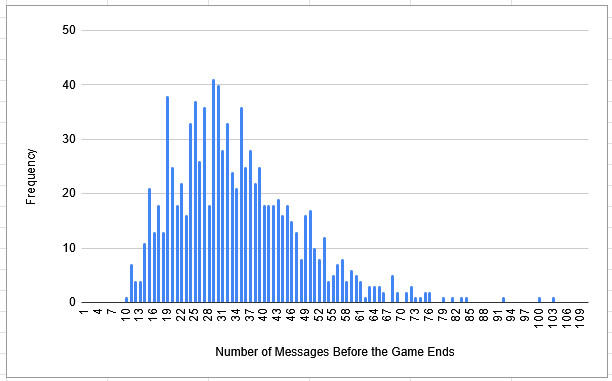

Inspired by the blog Skeleton Code Machine, which frequently uses Python to simulate game outcomes, I asked my friend Suntooth to help me write a program to simulate the number of rolls that 1,000 games of Goodbye World might entail. Here’s what we got:

As you can see, the results are all over the place. The range of this simulation was 10-103 messages, but it dawned on me that a game could literally go on forever were a player unlucky enough (or lucky enough, maybe, it does mean they don't die!).

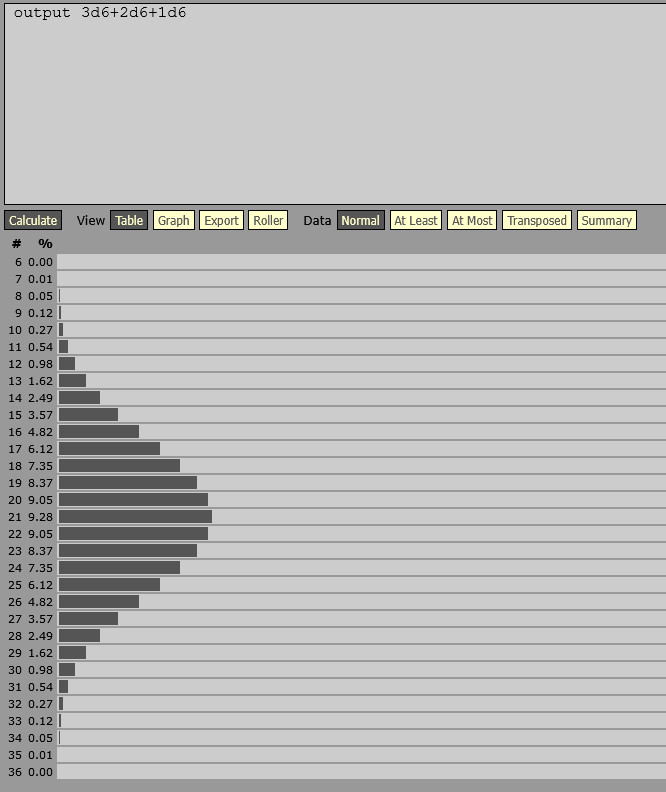

Either way, that completely ruined the dramatic pacing I was going for with the game. So I redesigned it to use the d6 pool system I described earlier. In this system, the game now had a concrete range to the number of messages you would send, the range of 6d6:

I managed to simulate this one all by myself :)

This was a vast improvement to the previous version. The new range was large enough to create strong tension without keeping the players for so long that the tension fizzled out. The games are quick but absolutely packed with high-emotion roleplay, precisely because you know that time is running short.

My lesson here is: consider the upper and lower bounds of the randomness in your game, and the experience a player might have if they have the absolute worst or best luck. Does it feel like the game goes too long (like Blue Prince)? Or that it flies by (like The Librarian's Apprentice)? Even if a combination of outcomes is incredibly unlikely, it might happen to someone, and you should keep that person in mind when designing your game.

It's also worth mentioning that different people have different tolerance levels for weird pacing like this. I'm very aware that I gave up on Blue Prince quite quickly. But I guess my point is that those unlikely outcomes are worth remembering when you design.

I really enjoyed Tom Francis’ video Blue Prince and its awkward relationship with hunches, I’d definitely recommend watching the full thing for a deeper dive into how random progression affects the experience of playing knowledge games like that specifically.

Also huge thanks to Suntooth for helping me with some of the dice simulation. Check out more from him at https://suntooth.online/.

This blog post was adapted from a Bluesky thread I made in May 2025, read the original here.

Thanks for reading!

CJ